By clicking submit, I consent to my personal data being collected, stored, and processed by Think Pacific in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Oral History’s Place in the Pacific

Oral History’s Place in the Pacific.

History ‘books’ by their very definition provide a written account of history. Yet, if part of history wasn’t written down, does that make it any less valid?

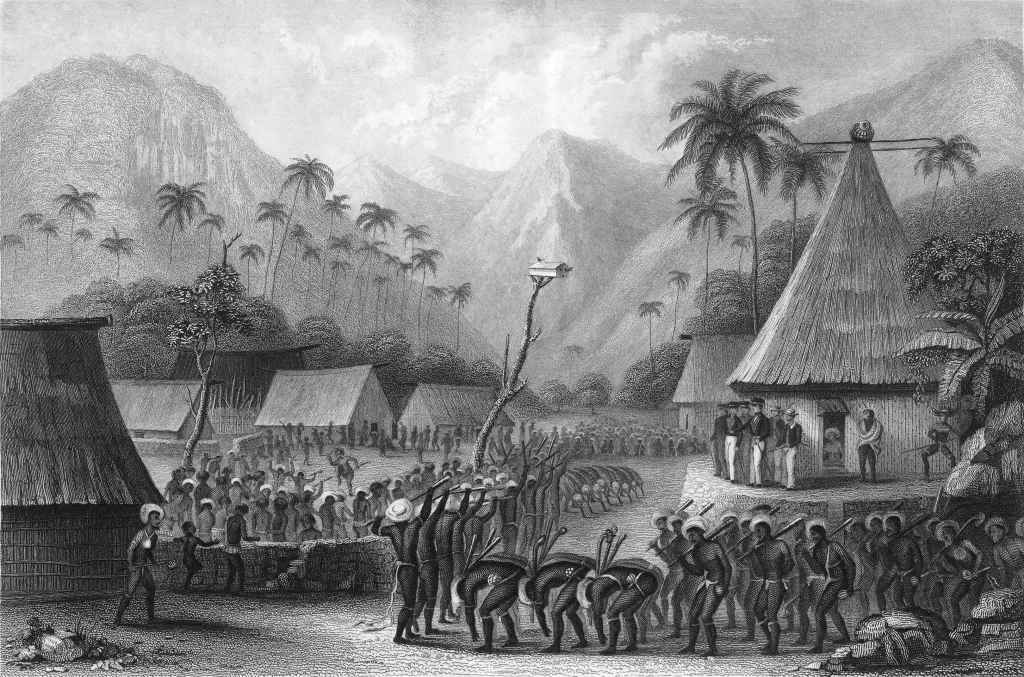

Throughout the history of the Pacific, very little was written; nothing was really written in Fiji until the second quarter of the 19th Century. People instead communicated their history through song, dance and stories in a vibrant and lively oral tradition. Rather than huddling behind pages of a favourite story book, children instead would listen to stories recited by their grandparents or learn about the history of their village through physically enacting the tale in a meke. Those children, in time, would soon become elders who would then repeat the process, the system transferring information from generation to generation.

As our resident Fijian culture expert Lulu likes to say, oral tradition acts as “a living archive of history.”

Strong words… yet oral tradition has historically been on the decline in Fiji. After the introduction of Western systems of literacy from Wesleyan missionaries in the 1830s, the imperatives to maintain an oral tradition have supposedly vanished in modern day Fiji… it has essentially been made redundant. When you can write something down permanently, why go through the hassle of retelling the story and remembering it from generation to generation?

During colonial times, Western lifestyle and systems of thought were adopted in Fiji rapidly, to some extent supplanting the old. As evident in the texts written, some missionaries by nature brought with them some air of superiority over the existing traditions of Fiji, both in religious aspects and consequently lifestyle. Their mindset surrounding the changes Fiji was about to encounter, from ‘dark to light’, from ‘superstition to knowledge’, was arguably transferred to Fijian collective consciousness in the steady process of Christianisation and Westernisation. Oral tradition, particularly those regarding myths related to the previous religion of Fiji, became seen as ‘old, superstitious and inaccurate’.

An immediate effect of this in the modern day, due to the marginalisation of oral tradition, is that certain traditions are only remembered in fragments in rural areas by older members of the community. Stories potentially containing valuable information are lost with the passing of time, disregarded or looked down upon in Western-style academia.

It is easy to look at the subject with doom and gloom, but despite a tendency to lean towards written tradition as the go to for history in academia, attitudes towards ancient stories are beginning to shift.

Oral traditions in Fiji can provide insights into history far earlier than the first texts. It is estimated that Fiji has been occupied for roughly 3000 years and oral traditions often address that side of history rather than the last 200! And they can be very accurate.

One relatively recent example of this knowledge coming to fruition is the tale of the now sunken ‘mythical’ island Vuniivilevu in the Davetalevu passage (between Viti Levu and Vanua Levu). The story is elaborate and contains characters of Fijian mythology that are well known across the archipelago, even if versions of the same story vary, but the basics of the story remain the same, travelling in a canoe called Rogovoka from the landing site, through central Fiji and continuing on to Tonga. According to the origin tale told by the people of Moturiki, one group from the original migration to Fiji (of which there are various versions of the tale from various groups in Fiji) travelled and settled on a small island called Vuniivilevu. Following their settlement, the island sunk, leaving survivors flailing in the water. Three survivors, two brothers and their sister, were said to drift with the current to the shores of Moturiki and they became the ancestors of the people of the Island today.

In 2002, following excavations in areas that were mentioned in the tale, a complete human skeleton of a woman was found in Naitabale who radiocarbon tests suggest could have lived around 950BC. The dates would have aligned with the migration of the Lapita people, an ancient group that migrated from East Asia through Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and continued through Fiji further East. These are indeed likely to have been the first people to settle in Fiji and their pattern of migration matches the story recited by Moturiki elders perfectly.

What’s even more impressive is that this story survived through scrutiny from outside influences. A common belief told now through oral tradition in Fiji is that ancestors of the ethnic Fijian population originated in Africa, migrating from Egypt. This has now been revealed, through contemporary anthropology, to be a narrative generated by 19th Century Missionaries who utilised popular models of anthropology at the time to explain the roots of the Fijian people; this version of Fijian history was taught during the training of Fijian priests and soon found itself embedded in the transfer of knowledge through oral tradition and has survived largely unquestioned to this day.

Both the inaccurate version of Fijian history and the upheld corrected version have their source in European scholarship, the irony is palpable! Fijian perspective in this case, as it arguably has been in the last 200 years, is the victim to external dictation from a source which ultimately represented authority at the time.

But don’t get me wrong, early books are still incredibly valuable. Through reading an example such as the one above, it is easy to see Western style scholarship, written tradition, as the bad guy. The ownership claim of accepted knowledge made by the early Western settlers may not have been appropriate at all, but it is important to not disregard the value of the texts they wrote.

Although somewhat biased, they remain untarnished written records and accounts of events, opinions on those events, recordings of other people’s opinions of those events, etc. In the 19th century, when ‘Westerners’ first encountered Fiji, they wrote down what they saw. Missionaries put on their anthropologist hats and recorded the scenes they witnessed before them. With appropriate source criticism (as we would also encounter any oral tradition with) we can draw very valuable information from books they wrote on certain subjects but also from letters and reports sent back to missionary societies.

Written history, in this aspect, ensures that knowledge is maintained in the eternal binding of ink to paper, or even nowadays, keyboard to screen. This becomes particularly apparent when certain traditions and features of society are spoken of less in contemporary Fijian communities after being deemed ‘dark’ through narratives generated by missionaries and the adopted Christian faith. When spoken of less, the oral tradition fades over time and with it the memory of the past. On subjects such as discontinued ceremonies (like the wife-strangling ceremony ‘loloku’) or features of a village that no longer exist (such as the ‘bure ni sa’), those written accounts are extremely valuable in painting an accurate history.

Ultimately, throughout this blog it feels like I have weighed oral tradition up in competition with the written, but that shouldn’t be the case.

Written tradition and oral tradition are both means of maintaining history in different forms; both are malleable, both are subject to source criticism and both can be used in the pursuit of truth. The importance of approaching topics of Fijian history with both lenses is paramount and a genuine pursuit of an understanding of history in Fiji would never disregard either sources at face value.

After all, does a story have to be completely factually correct to provide an element of truth? What are deemed as ‘myths’ in Fiji may touch on significant points of history and provide factual insight to some extent, but they also importantly tell you of the reaction of that community to the event and the motives and opinions that still influence people’s perspectives to this day. They are concerned with morals and cultural integrity, origin and identity.

The events that generated the transition from exclusively oral tradition to a widely adopted written tradition in Fiji mean that a written account of history certainly comes with the package of a wider colonial narrative, associating itself with the power dynamics of such a situation.

Perhaps oral tradition plays a bigger role in Fiji regaining ownership of its own history.

Cam Watson

Think Pacific Coordinator

Research Student: MPhil Religion & Theology, Bristol University