By clicking submit, I consent to my personal data being collected, stored, and processed by Think Pacific in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

A National Perspective: Natural Disasters

As a Small Island Developing State, Fiji is severely impacted by both the slow and sudden onsets of climate change induced by global dependence on unsustainable fossil fuels. Rising sea levels engulfing low-lying coastal communities, saltwater intrusion reducing arable land, changing weather patterns impacting food security, and catastrophic cyclones reversing years of development progress while threatening fiscal stability are some of the major climate-induced adversities Fiji faces. These adversities tremendously impact sustainable livelihoods, security and well-being and contribute to an increased incidence of poverty and undue pressure on social services.

Cyclone Winston was the biggest cyclone ever recorded in the Southern Hemisphere, and swept through Fiji in February 2016.

Was the total amount of damage caused.

People sadly lost their lives.

People were significantly impacted by Cyclone Winston.

After Cyclone Winston hit Fiji in 2016, Think Pacific coordinated a relief mission to provide vital resources throughout remote areas in Fiji. As part of this effort, Think Pacific partnered with Rotary Fiji to donate clothing to Koro Island, one of the worst hit communities. Watch our documentary to learn more and to hear stories from those affected by this devastating storm.

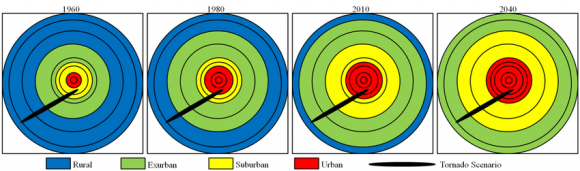

‘The Expanding Bullseye’ theory suggests that the increasing financial damage seen as a result of natural disasters may be due to changes in society that have resulted in denser populations in climate vulnerable areas and an increase in infrastructure in these locations.

Thoughts: How can we adapt and limit the costs of natural disasters?

Launched at the COP23 Climate event, this document was produced in partnership with the World Bank and the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR).

‘At least USD 80 billion in crop and livestock production has been lost in developing countries over the past decade after disasters (FAO)’.

This highlights the importance of developing our food security in order to sustain life…

The Guardian: When Tropical Cyclone Winston struck Abhishek Sapra’s farm exactly four years ago, the damage was monumental. Sapra suffered losses of over $F500,000 (US$227,000).

“The trees were stripped of all their leaves, a lot of heritage trees fell over, crops were almost completely wiped out,” says Sapra. “Unless it was underground it didn’t survive.”

'Damage to crops and livestock is estimated at USD 104 million, while damages to fisheries are also critical. With much of the country relying on subsistence production to meet their food needs, restoring agriculture and fishery-based livelihoods is essential to avoid dependency on food aid in the coming months'

Under the UNFCCC and IPCC’s categories, Fiji is categorised as a ‘vulnerable’ small island nation under serious threat from various climate change impacts. This includes the rise in sea level and extreme weather events.

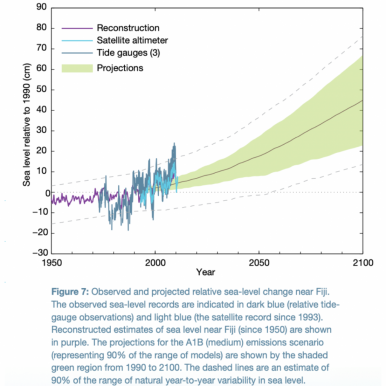

Climate change threatens the sustainability and habitability of coastal communities and environments. In 2018, researchers reported that the world’s mean sea level had risen by more than seven centimetres since 1993 due to the expansion of warming ocean waters and melting ice sheets and glaciers. Should atmospheric CO2 concentration continue to rise rapidly, sea levels could rise up to one metre by 2100.

The Government of Fiji has indicated that 830 vulnerable communities require relocation due to risks from climate-related impacts. Of these, 48 communities have been identified as being in urgent need of relocation.

In 2014, residents of the small village of Vunidogoloa in Fiji were left with no choice but to relocate. Their village had been experiencing increasing coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion, and flooding over recent years.

With the support of the Government of Fiji and international agencies, they relocated to higher lands two kilometers from their old home. While some infrastructure still needs to be built, relocation has reduced their exposure to climate risks and protected the community’s future.

Planned relocation in Fiji is a relatively new response to the effects of climate change, and it is only viewed as a last resort. Relocation is a complex process and can be traumatic for those involved. It is not just a case of economics and physical structures, there are a number of complex, non-tangible aspects associated with relocation, which can include challenges to identity, as well as various psychological, social, emotional and cultural damages.

As ocean water warms it expands causing the sea level to rise. Instruments mounted on satellites and tide gauges are used to measure sea level. Satellite data indicate sea level has risen in Fiji by about 6 mm per year since 1993. This is larger than the global average of 2.8–3.6 mm per year. This higher rate of rise may be partly related to natural fluctuations that take place year to year or decade to decade caused by phenomena such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. The natural variation in sea level can be seen in Figure 7 which includes the tide gauge record since 1972 and the satellite data since 1993.

Saltwater intrusion has huge impacts on sugar cane farmers. With sugar cane as Fiji’s most prominent export, the longer-term impacts here could be devastating.

Saltwater intrusion from coastal flooding destroys farmland, disrupting the supply of staples in the Fijian economy and forcing communities to migrate to safer ground. The damages sustained to Viti Levu, Fiji’s most populous island, total some $52 million per year, or 4 percent of Fiji’s GDP.

Saltwater intrusion contributed to the relocation of Vunidogoloa.

Watch this video which explores the impacts of climate change at a community level.

Annual maximum and minimum temperatures have increased in both Suva and Nadi since 1950. In Suva, maximum temperatures have increased at a rate of 0.15°C per decade and at Nadi Airport the rate of increase has been 0.18°C per decade. These temperature increases are consistent with the global pattern of warming.

About one-quarter of the carbon dioxide emitted from human activities each year is absorbed by the oceans. As the extra carbon dioxide reacts with seawater it causes the ocean to become slightly more acidic. This impacts the growth of corals and organisms that construct their skeletons from carbonate minerals. These species are critical to the balance of tropical reef ecosystems. Data shows that since the 18th century the level of ocean acidification has been slowly increasing in Fiji’s waters.

Tropical cyclones usually affect Fiji between November and April, and occasionally in October and May in El Niño years. In the 41-year period between 1969 and 2010, 70 tropical cyclones passed within 400 km of Suva, an average of one to two cyclones per season. Over this period, cyclones occurred more frequently in El Niño years.

Mangroves act as a natural sea wall, protecting water from rising up into farms, and create habitats for marine life to live. This is an example of natural engineering, where perhaps instead of encouraging the building of concrete sea walls, we could look at how to plant more mangroves to benefit both the marine life and the local community.

Lessons From Fiji: Financing Climate Resilience

To build a decarbonised, climate-resilient economy, countries first need to understand where their current climate finance is flowing. Because climate finance flows from a range of sources to a plethora of institutions and projects, decision-makers in many countries do not have enough information to coordinate various forms of support or effectively allocate available domestic and international funding.

Understanding where more funds are needed can set countries up for greater success in accessing and channeling money. Fiji is using the Climate Finance Snapshot as the foundation for its Climate Finance Country Program, which will guide the Fijian government and its development partners by detailing priority investments in climate-resilient and low-emissions activities over the next five to seven years.

Fiji’s experience with the Snapshot has helped the government understand how to work around data gaps and improve processes for tracking climate finance. To complement the Snapshot, Fiji has embarked on efforts to systematically tag climate-related expenditures in its budgeting process, so that the government can track climate finance more efficiently and accurately in the future. Fiji has also launched other initiatives to improve its systematic tracking of climate finance. For example, Fiji is developing a climate expenditure typology to isolate Fiji’s climate related spending from its development expenditure. Fiji is working on incorporating climate expenditure codes into its public financial management system and is strengthening its use of digital platforms to better track climate finance from its overseas development assistance.